Is time-restricted eating more effective than calorie counting for weight loss? Original paper

In this year-long randomized controlled study, time-restricted eating was as effective as intentional calorie restriction for weight loss, even though the participants in the time-restricted eating group weren’t specifically told to reduce their calorie intake.

This Study Summary was published on November 1, 2023.

Quick Summary

In this year-long randomized controlled study, time-restricted eating was as effective as intentional calorie restriction for weight loss, even though the participants in the time-restricted eating group weren’t specifically told to reduce their calorie intake.

What was studied?

The effectiveness of time-restricting eating without calorie counting on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults with obesity.

The primary outcome was body weight. The prespecified secondary outcomes included changes in fat mass, lean mass, visceral fat mass, bone density, blood pressure, heart rate, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR (a measure of insulin resistance), quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI, a measure of insulin sensitivity), HbA1c, and calorie intake.

Who was studied?

A racially diverse group of 90 adults with obesity (average age of 44; 82% women, 18% men) comprising Black (30 participants), Asian (6 participants), Hispanic (41 participants), and white (13 participants) adults (terms used by the study authors).

How was it studied?

In this 12-month randomized controlled trial, participants were assigned to one of the following groups: time-restricted eating (TRE), calorie restriction (CR), or a control group (no dietary intervention).

The TRE group was instructed to consume all of their daily meals within an 8-hour window (between noon and 8 p.m.) but were not given instructions to count calories.

The CR group was instructed to reduce their calorie intake by 25% per day below their estimated calorie requirements for weight maintenance.

The control group was instructed to maintain their usual diet, which included an eating window of 10 hours or more each day without calorie counting.

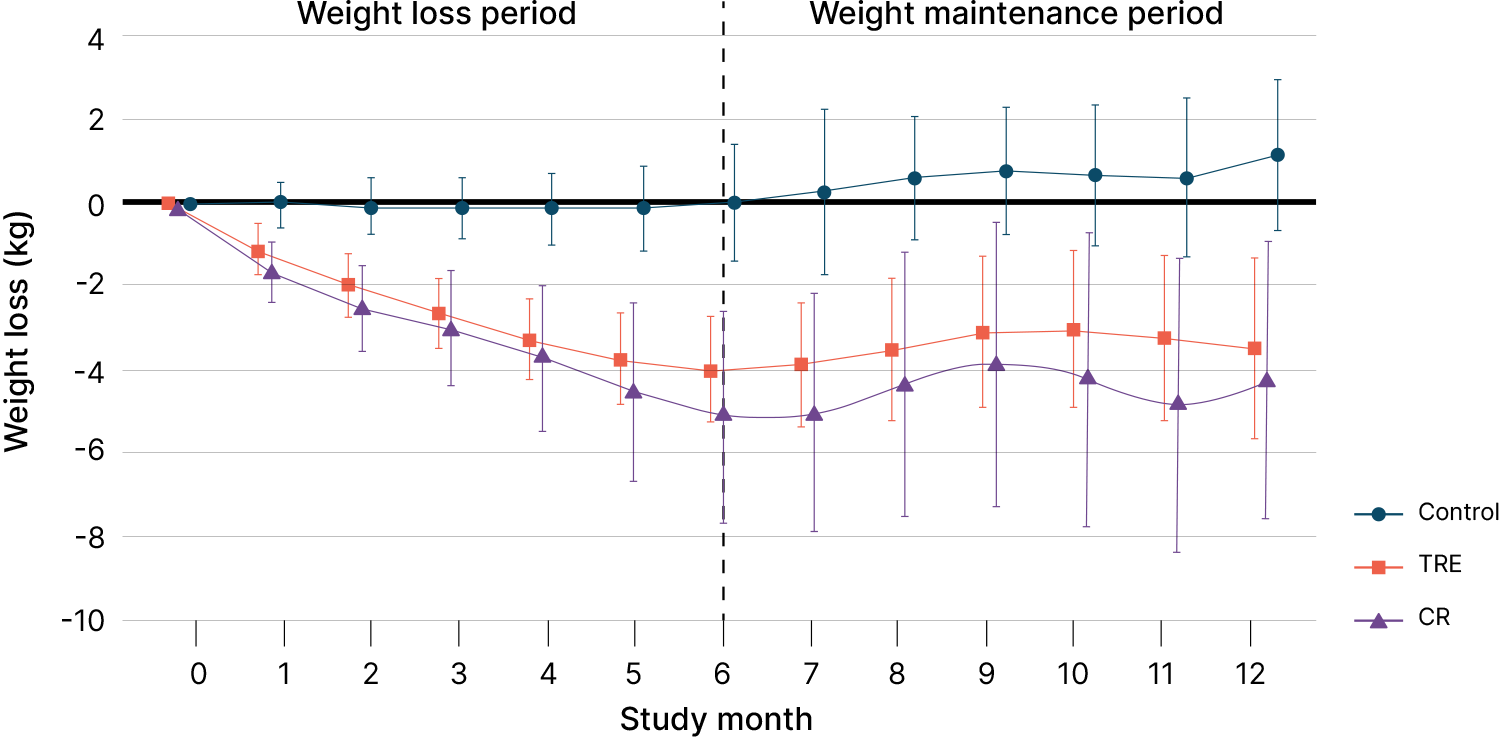

The first 6 months of the study served as a weight-loss phase, while the second 6 months served as a weight-maintenance phase, during which participants in the TRE group extended their eating window to 10 hours per day and the CR group consumed 100% of their estimated calorie needs each day.

What were the results?

Compared to the control group, the TRE group lost 4.6 kg (10.1 lb) and the CR group lost 5.4 kg (11.9 lb).

Time restricted eating (TRE) and calorie restriction (CR) result in similar weight loss over 12 months

TRE and CR both reduced fat mass (−2.8 kg and −3.2 kg, respectively), waist circumference (−4.9 and −2.3 cm), and BMI (−1.7 and −2.0) compared to the control group.

TRE, but not CR, improved insulin sensitivity compared to the control group. None of the other outcomes were different between groups.

The TRE group reduced calorie intake by an average of 425 kcal per day, and the CR groups reduced calorie intake by an average of 405 kcal per day.

The big picture

A variant of the popular intermittent fasting eating strategy, time-restricted eating is a dietary regimen that involves limiting the eating window, most often to a period of 4–8 hours during the day, with the remainder of the time spent fasting or consuming calorie-free beverages like water, coffee, tea, and diet soda.

There have been only a few studies that have compared the effects of TRE to traditional dietary restriction, also known as calorie restriction or CR.

In a year-long study in adults with obesity that compared an 8-hour TRE (i.e., 16:8 intermittent fasting plus CR intervention to a CR-only intervention, both diets led to similar weight loss: 8 kg for the TRE group and 6.3 kg for the CR-only group.[1] Both diets consisted of 1,500–1,800 kcal/day for men and 1,200–1,500 kcal/day for women.

An 8-week randomized controlled study in adults with obesity also found similar reductions in weight when comparing TRE (10-hour eating window between 10 a.m. and 8 p.m.) to CR without TRE (12-hour eating window). The results showed that TRE led to an 8.5% reduction in body weight, while CR without TRE resulted in a 7.1% reduction in body weight compared to baseline.[2] Notably, TRE reduced fasting blood glucose by 7.6 mg/dL, while no significant improvements were observed in the CR group, indicating that TRE may have unique benefits for glycemic control.

Finally, a 39-week study comparing early TRE (10-hour eating window beginning within 3 hours of waking up) plus CR to CR-only (approximately 35% calorie restriction) found no differences between groups for weight loss, which was 4.9 kg in the TRE-CR groups and 4.3 kg in the CR-only groups.[3]

Cumulatively, these studies suggest that in the context of a calorie-restricted diet, the addition of TRE doesn’t have an additional benefit on weight loss or other cardiometabolic risk factors, at least when compared to traditional CR. The amount of “calories in” appears to matter more than “when” those calories are coming in.

But the main attraction of TRE versus traditional CR seems to be adherence. It’s a much simpler way to reduce daily calorie intake and might therefore be a better way to maintain weight loss over time. Most diets fail in the long run. But why is long-term weight loss — or weight loss maintenance — so difficult? And could TRE provide a solution?

First, the modern food environment, which is characterized by an abundance of ultraprocessed foods, seems to encourage overconsumption. When this environment is paired with modern conveniences that make physical activity difficult and sedentary activity the norm, weight management can be an extremely challenging endeavor.[4]

Second, diets are hard to stick to. One of the main reasons why people don’t maintain CR is that counting calories (and actually reducing intake) can be burdensome, not to mention difficult and inaccurate, especially in the modern obesogenic environment. TRE can remedy the difficulties of counting calories by providing an easy alternative of just watching the clock.

Indeed, studies show that when people limit their daily eating window to 4–8 hours each day, they tend to unintentionally reduce calories by about 350–500 per day.[5][6] When there’s less time to eat, calorie intake drops. The good news, as suggested by this and other studies, is that the feeding window doesn’t have to be dramatically restricted — going from 10–12 hours to 8 hours of eating per day seems to be effective. In fact, 8 hours seems to result in a similar reduction in calorie intake (about 500 kcal/day) as 4-hour and 6-hour TRE.[5][6]

Improved adherence may be one of TRE’s key distinctive features when compared to CR — it’s a simpler, more flexible dietary intervention that allows individuals to maintain their usual diet composition within their eating window and only requires them to track when and for how long — rather than how much — they are eating. This is hypothesized to reduce the cognitive effort of dieting and increase adherence and dietary satisfaction.[7]

Adherence to various forms of TRE has been reported to be around 63% to 100%, albeit over shorter time periods (4 to 24 weeks).[8] And while few studies have compared TRE and CR in terms of their adherence rates, in the current study, participants in the TRE group reported adhering to their eating window 87% of the time over the 12-month study, compared to only 61% of participants in the CR group who reported adhering to their caloric goal.

Overall, though biopsychosocial models and participant subjective reports indicate that TRE could be more sustainable in the long term, future trials directly comparing adherence between CR and TRE are needed.

This study is novel and important for a few reasons:

- It included a racially diverse participant population, which increases the generalizability of the results compared to previously published fasting studies.

- The TRE window — strategically placed between noon and 8 p.m. — seems to align better with what people actually do in daily life. Previous TRE studies could be criticized for using an eating window that ends too early (e.g., at 4 p.m.), which would place barriers on an individual’s ability to participate in social and family gatherings surrounding food.

- Calorie counting wasn’t explicitly encouraged for the TRE group, nor were they given instructions on the amount and types of food to eat.

All of the above factors improve the applicability of this intervention for individuals trying to lose weight and the health professionals guiding them on how to do so. Ultimately, if weight loss is going to be sustainable, the intervention used to achieve it also needs to be sustainable.

While TRE may not be better than traditional CR for weight loss, some people may find it a worthwhile alternative to conventional dieting in terms of its feasibility, especially if it proves to have long-term sustainability.

Anything else I need to know?

The analyses of the secondary study outcomes weren’t adjusted for multiple comparisons, and therefore, the results for these outcomes should be considered exploratory.

This Study Summary was published on November 1, 2023.

References

- ^Deying Liu, Yan Huang, Chensihan Huang, Shunyu Yang, Xueyun Wei, Peizhen Zhang, Dan Guo, Jiayang Lin, Bingyan Xu, Changwei Li, Hua He, Jiang He, Shiqun Liu, Linna Shi, Yaoming Xue, Huijie ZhangCalorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight LossN Engl J Med.(2022 Apr 21)

- ^Pamela M Peeke, Frank L Greenway, Sonja K Billes, Dachuan Zhang, Ken FujiokaEffect of time restricted eating on body weight and fasting glucose in participants with obesity: results of a randomized, controlled, virtual clinical trialNutr Diabetes.(2021 Jan 15)

- ^Thomas EA, Zaman A, Sloggett KJ, Steinke S, Grau L, Catenacci VA, Cornier MA, Rynders CAEarly time-restricted eating compared with daily caloric restriction: A randomized trial in adults with obesity.Obesity (Silver Spring).(2022-May)

- ^Hall KD, Kahan SMaintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of ObesityMed Clin North Am.(2018 Jan)

- ^Kelsey Gabel, Kristin K Hoddy, Nicole Haggerty, Jeehee Song, Cynthia M Kroeger, John F Trepanowski, Satchidananda Panda, Krista A VaradyEffects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot studyNutr Healthy Aging.(2018 Jun 15)

- ^Sofia Cienfuegos, Kelsey Gabel, Faiza Kalam, Mark Ezpeleta, Eric Wiseman, Vasiliki Pavlou, Shuhao Lin, Manoela Lima Oliveira, Krista A VaradyEffects of 4- and 6-h Time-Restricted Feeding on Weight and Cardiometabolic Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with ObesityCell Metab.(2020 Sep 1)

- ^O'Connor SG, Boyd P, Bailey CP, Shams-White MM, Agurs-Collins T, Hall K, Reedy J, Sauter ER, Czajkowski SMPerspective: Time-Restricted Eating Compared with Caloric Restriction: Potential Facilitators and Barriers of Long-Term Weight Loss Maintenance.Adv Nutr.(2021-Mar-31)

- ^Jefcoate PW, Robertson MD, Ogden J, Johnston JDExploring Rates of Adherence and Barriers to Time-Restricted Eating.Nutrients.(2023-May-16)