Is dieting with meal replacements better than just dieting?

Meal replacements held a slight but statistically significant advantage over low-calorie diets for weight loss, but the results weren’t different compared to very-low-calorie diets. Replacing more food-based meals tended to yield better weight loss outcomes.

Last Updated: February 1, 2022

Become an Examine+ member to get full access to the Examine Database, Study Summaries, and Supplement Guides.

Try for free for 7 days and stay on top of the latest research.

Is a diet using meal replacements more effective for weight loss in comparison with food-based calorie-restricted diets? If so, which factors determine the success of this strategy?

Meal replacements (MR) consist of pre-packaged or pre-made food products that are used to replace normally consumed meals in the diet in order to reduce total energy intake and facilitate weight loss. In contrast to food-based diets, weight loss diets incorporating MR might be[1] easier to adhere and control. It has been previously shown that energy-restricted diets that use MR appear to be[2] more effective than comparable energy-restricted food-based diets. However, no previous meta-analysis has determined if there are important treatment-related characteristics that might help in success with MR diets, like the timespan the participants followed these diets, the number of MR per day, or the total energy derived from MR.

This was a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies that included data since 2000. It was not preregistered. The primary outcome was change in BMI or weight. Researchers evaluated 22 interventions comparing meal replacement (MR) based on low-energy diets (LED; 1,000–1,500 kcals per day) to food-based LED, and two interventions comparing MR based on very-low-energy diets (VLED; 600–800 kcals per day) to food-based VLED. The calorie content of the MR ranged from 270 to 1,200 kcal per day.

The meta-analysis used data from 1,982 adults with overweight or obesity (18–65 years old) from the United States, Germany, India, Taiwan, Australia, Republic of Korea, Brazil, and Singapore. Two studies were conducted exclusively with men, 6 with women, and 14 involved both sexes. The duration of the interventions ranged from 2 to 52 weeks. The type of MR included liquid formula, powdered mixes, soups, prepackaged food, and bars.

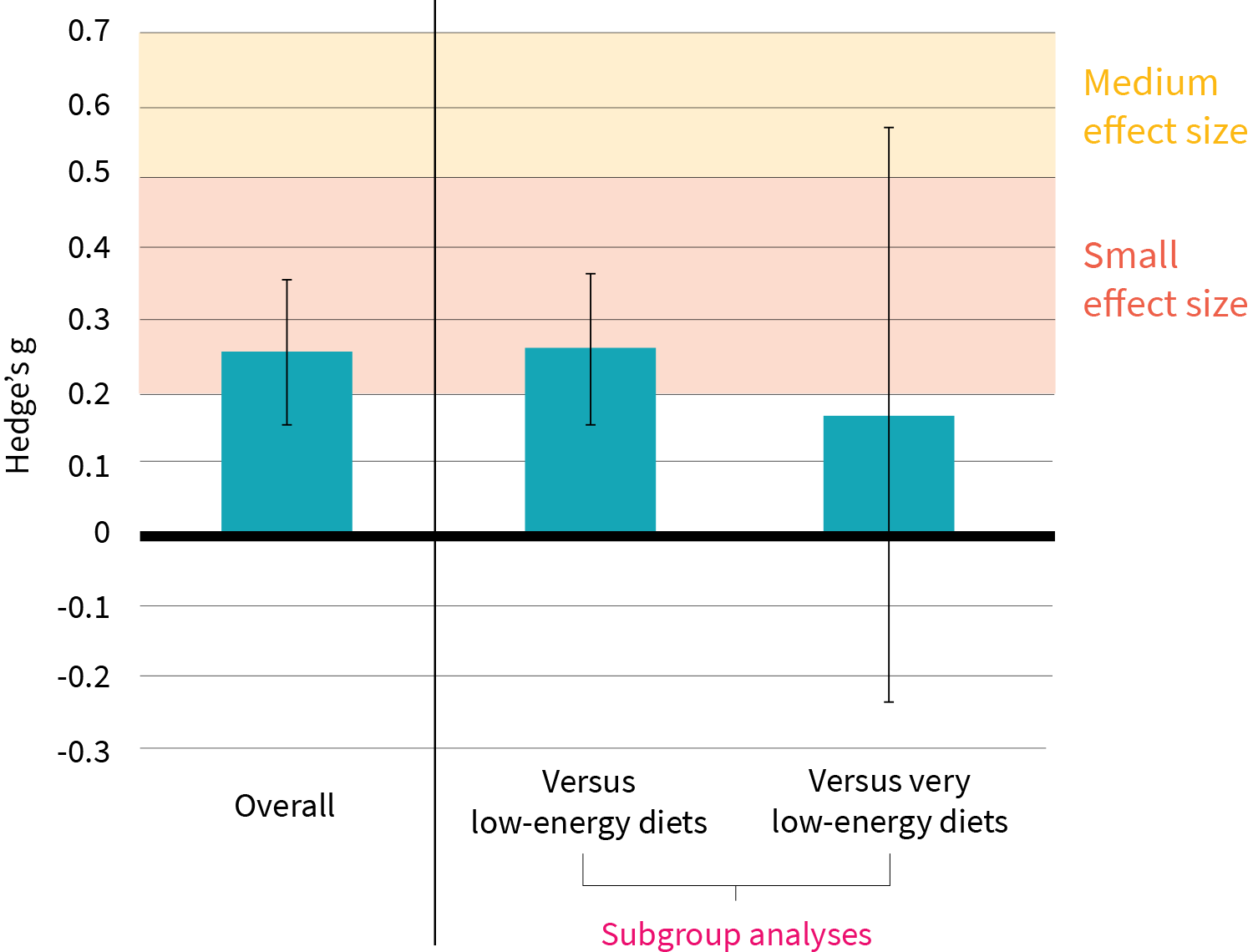

Effect sizes were pooled using random-effects meta-analysis and expressed as Hedges g (interpreted as small: 0.2–0.49, medium: 0.5–0.79, and large: 0.8 or above). Meta-regression and meta-ANOVA (using age, sex, initial BMI, duration of treatment, frequency of MR intake, and percentage of total energy intake from MR as moderators) were performed.

This meta-analysis included 22 randomized-controlled trials involving 1,982 adults with overweight or obesity from different parts of the world. The effect of replacing food with meal replacements (liquid formulas, powdered mixes, soups, prepackaged foods, and bars) on BMI or weight was the primary outcome. Researchers also evaluated the interaction of replacements with other treatment and participant-related variables.

As shown in Figure 1, the effect size for MR compared to conventional diets was small (g=0.255). When researchers compared low-energy diets, meta-ANOVA results showed a small effect size of MR over conventional diets (g=0.261), but no difference on very-low-energy diets.

Figure 1: Meal replacements’ overall effect on weight and compared to only low- and very-low-energy diets (with 95% confidence intervals)

Consuming a higher percentage of energy from MR (more than 60%) had a medium effect size (g=0.545) compared to food-based diets and had the greatest effect on weight loss, followed by the group consuming between 30 and 60% of energy from MR (g=0.232). Diets providing less than 30% of the total energy intake from MR didn’t facilitate significantly greater weight loss than food-based diets.

Figure 2: Effect of meal replacements on weight as percentage of total energy intake (with 95% confidence intervals)

Meta-regression showed that the strongest factors moderating the effects were the percentage of total daily energy intake derived from MR and the frequency of MR, where three MR per day had a bigger effect size (g=0.544) than two meals per day (g=0.177).

Overall, meal replacement diets had a weight loss advantage over food-based diets. A higher percentage of energy derived from meal replacements (at least 30%) and a higher number of meal replacements consumed per day was associated with significantly greater effect sizes, which corresponds to greater weight loss.

One of the main difficulties associated with energy-restricted diets is adherence. Replacing food with meal replacements might be[1] an easy way of reducing complexity of the diet, and thus increase adherence[3] to the energy restriction. The results of this meta-analysis are in line with this hypothesis, as there was a larger effect when most of the energy from a diet was consumed as meal replacements and when more meals per day were given as meal replacements. The advantage of MR-based diets appears[2] to extend to up to one year, so it constitutes a viable treatment option.

An important parameter that was not evaluated in the current study is the effects of meal replacement type (ie. powder, liquid or solid) and their nutritional composition. Also note that this study only analyzed weight loss, and not other important cardiometabolic risk or body composition parameters. Presumably, meal replacement will also improve these outcomes as most risk factors for cardiovascular disease improve[4] with weight loss, though how meal replacement components could differentially affect these risk factor markers also requires further study.

Replacing a great proportion of the diet with meal replacements might be a convenient way of adhering to an energy-restricted diet by reducing diet complexity. However, the efficacy of replacements might depend on the type of meal replacement (ie. liquid or solid) or their nutritional composition. Future studies will need to analyze if these are important for the effects of meal replacements on weight loss and other metabolic markers not analyzed in the present study.

When compared to food-based diets, low-energy diets containing at least 30–60% of calories derived from meal replacements appear to have an advantage for weight loss, with higher meal replacement use having stronger effects. Further research is needed to determine whether meal replacement type and composition affects both weight loss as well as cardiometabolic risk factors.